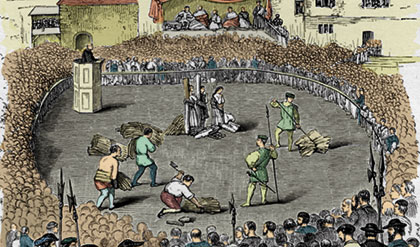

[ABOVE—Anne Askew and others at the stake, from Thomas Armitage’s A History of the Baptists (New York: Bryan, Taylor and Co., 1893), colorized.]

Her saga began with a forced marriage, her father having compelled her to take the place of an older sister as bride to Thomas Kyme (the older sister had died). Anne and Kyme never hit it off. In part their difficulties were because he was Catholic, she Protestant.

She left home and was public enough about her religious views— which disagreed with those of king and church— that she was arrested and returned to her husband, who was charged to keep her in check.

Six half-hour programs vividly bring to life the Reformation Overview, and covers seven colorful reform leaders.

One suspects that Anne’s tart tongue made her tough to live with. Although Kyme called her the most devout woman he had ever known, he threw her out of the house. Soon afterward, she was again arrested and this time examined under torture about her associates, whom she did not betray. Published accounts of her hearings appeared in the writings of John Bale and in Foxe’s Actes and Monuments (Book of Martyrs).

Eventually her views took her to the stake. Given one last chance to recant and escape the fire, she replied, “I came not here to deny my Lord and Savior.”

The following excerpt has been revised a little to make it more readable to modern audiences.

The effect of my examination and handling, since my departure from Newgate.

On Tuesday I was sent from Newgate to the Sign of the Crown, where Master Rich and the Bishop of London with all their power and flattering words, went about to persuade me from God. But I did not esteem their glossing pretences.

Then Nicolas Shaxton came to me, and counseled me to recant as he had done. Then I said to him, that it had been good for him, never to have been born with many other like words.

Then master Rich sent me to the tower, where I remained til 3 o’clock. Then came Rich and one of the council, charging me upon my obedience, to show unto them, if I knew man or woman of my sect. My answer was, that I knew none. Then they asked me of my Lady of Suffolk, my Lady Sussex, my Lady of Hertford, my Lady Denny and my Lady Fizwilliams. I said, if I should pronounce any thing against them, that I was not able to prove it.

Then said they unto me, that the king was informed, that I could name, if I would, a great number of my sect. Then I answered, that the king was as well deceived in that behalf, as dissembled within other matters. Then they commanded me to show how I was maintained in the counter, and who willed me to stick by my opinion. I said that there was no creature that did strengthen me therein. And as for the help that I had in the counter, it was by the means of my maid. For as she went abroad in the streets, she made moan to the apprentices, and they by her did send me money. But who they were I never knew.

Then they said, that there were various gentlewomen who gave me money. But I knew not their names. Then they said that there were various ladies, who had sent me money.

I answered, that there was a man in a blue coat, who delivered me ten shillings, and [who] said that my Lady of Hertford sent it me. And another in a violet coat did geve me eight shillings, and said that my Lady Denny sent it me. Whether it were true or no, I cannot tell. For I am not sure who sent it me, but as the maid did say.

Then they said, there were [members] of the council that did maintain me. And I said, no.

Then they did put me on the rack, because I confessed no ladies or gentlewomen to be of my opinion, and they kept me on it a long time. And because I lay still and did not cry, my Lord Chancellor and Master Rich, took pains to rack me with their own hands, till I was almost dead. Then the lieutenant caused me to be loosed from the rack. Incontinently I swooned, and then they revived me again.

After that I sat two long hours upon the bare floor, reasoning with my Lord Chancellor, whereas he with many flattering words, urged me to leave my opinion. But my Lord God (I thank his everlasting goodness) gave me grace to persevere and will do (I hope) to the very end. Then was I brought to a house, and laid in a bed with as weary and painful bones, as ever had patient Job. I thank my Lord God for it. Then my Lord Chancellor sent me word if I would leave my opinion, I should want nothing. If I would not, I should [be sent] forth to Newgate, and so be burned.

I sent him again word, that I would rather die, than to break my faith. [Through this may] the Lord open the eyes of their blind hearts, that the truth may take place.

Farewell dear friend, and pray pray, pray.