On his way from England to Portugal to survey the damage done by the great Lisbon earthquake, John Howard was captured by a French privateer. He was cruelly treated. He wrote, “Before we reached Brest I suffered the extremity of thirst, not having for above forty hours one drop of water, nor scarcely a morsel of food. In the castle at Brest I lay six nights upon straw, and observed how cruelly my countrymen were used there and at Morlaix, whither I was carried next; during two months I was at Carhaix upon parole, I corresponded with the English prisoners at Brest, Morlaix, and Dinnan: at the last of these towns were several of our ship’s crew, and my servant. I had sufficient evidence of their being treated with such barbarity that many hundreds had perished, and that thirty-six were buried in a hole at Dinnan in one day.” At Brest the prisoners were kept for a long time without food; at last a joint of mutton was thrown into the filthy dungeon, which the prisoners were obliged to tear to pieces and gnaw like dogs. At Carhaix, where he spent two months on parole, an utter stranger had to provide him with both clothes and money—for he had been stripped of his belongings at Brest.

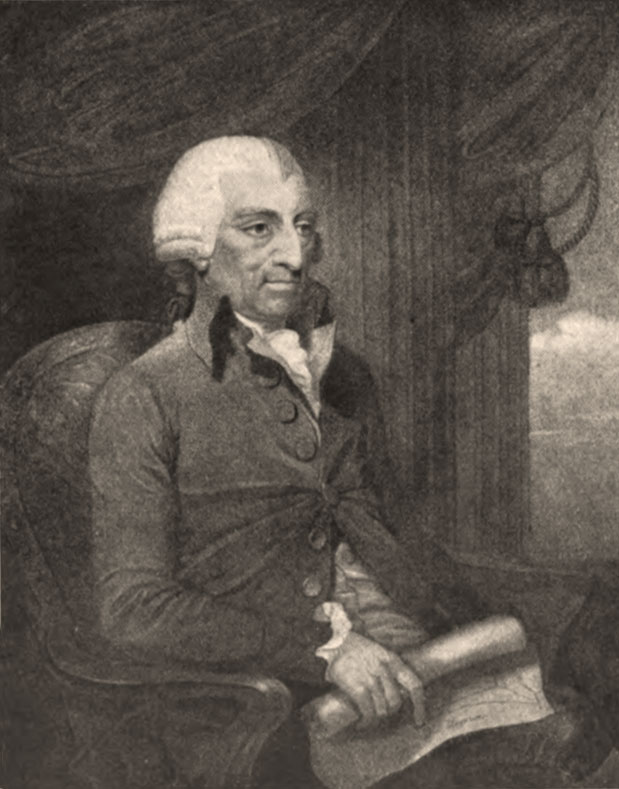

Later, Howard was elected sheriff of Bedford. Discovering the bad state of the county prisons, he set out to remedy not only those in his immediate sphere, but throughout all Europe. Edmund Burke summed up Howard’s contribution in a speech to parliament, noting that Howard toured Europe not to view grandeur or increase his own wealth, “but to dive into the depths of dungeons, to plunge into the infection of hospitals, to survey the mansions of sorrow and pain; to take the gauge and dimensions of misery, depression, and contempt; to remember the forgotten, to attend to the neglected, to visit the forsaken, and to compare and collate the distresses of all men in all countries.”