John Knox was at the wrong place at the wrong time. He was in St. Andrews castle when it fell to the French. He had gone inside the walls to continue the work he was paid for—tutoring. His employers were among those involved in the assassination of Cardinal Beaton, the brutal archbishop of Scotland who had burned Knox’s mentor, George Wishart, alive.

While in the castle, the nobles involved in the assassination put great pressure on Knox to become their chaplain. He wrestled with the idea but concluded it was a call from God. Consequently, although he had no part in the murder of Beaton, he was made a galley slave.

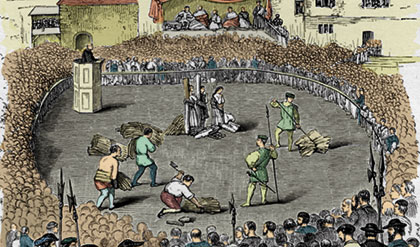

In the end of June, 1547, a French fleet, with a considerable body of land forces, under the command of Leo Strozzi, appeared before St. Andrews to assist the governor in the reduction of the castle. It was invested both by sea and land; and, being disappointed of the expected aid from England, the besieged, after a brave and vigorous resistance, were under the necessity of capitulating to the French commander on the last day of July. The terms which they obtained were honorable; the lives of all in the castle were to be spared; they were to be transported to France, and if they did not choose to enter into the service of the French king, were to be conveyed to any country which they might prefer, except Scotland.

John Rough had left them previous to the commencement of the siege, and retired to England. Knox, although he did not expect that the garrison would be able to hold out, could not prevail upon himself to desert his charge [the chaplaincy], and resolved to share with his brethren in the hazard of the siege. He was conveyed along with them on board the fleet, which, in a few days, set sail for France, arrived at Fecamp, and, going up the Seine, anchored before Rouen. The capitulation was violated, and they were all detained prisoners of war at the solicitation of the pope and Scottish clergy. The principal gentlemen were incarcerated in Rouen, Cherburg, Brest, and Mont St. Michel. Knox, with a few others, was confined on board the galleys; and in addition to the rigours of ordinary captivity, was loaded with chains, and exposed to all the indignities with which Papists were accustomed to treat those whom they regarded as heretics.

From Rouen they sailed to Nantes, and lay upon the Loire during the following winter. Solicitations, threatenings, and violence were all employed to induce the prisoners to change their religion, or at least to countenance the popish worship. But so great was their abhorrence of that system, that not a single individual of the whole company, on land or water, could be induced to symbolize in the smallest degree with idolaters. While the prison ships lay on the Loire, mass was frequently said, and salve regina sung on board, or on the shore within their hearing. On these occasions, they were brought out and threatened with the torture, if they did not give the usual signs of reverence; but instead of complying, they covered their heads as soon as the service began.

Knox has preserved in his history a humorous incident which took place on one of these occasions; and although he has not said so, it is highly probable that he himself was the person concerned in the affair. One day a fine painted image of the Virgin was brought into one of the galleys, and a Scotch prisoner was desired to give it the kiss of adoration. He refused, saying, that such idols were accursed, and he would not touch it. “But you shall,” replied one of the officers roughly, at the same time forcing it towards his mouth. Upon this the prisoner seized the image, and throwing it into the river, said, “Let our Lady now save herself; she is light enough, let her learn to swim.” The officers with difficulty saved their goddess from the waves: and the prisoners were relieved for the future from such troublesome importunities!

In summer 1548, as nearly as I can collect, the galleys in which they were confined returned to Scotland, and continued for a considerable time on the east coast, watching for English vessels. Knox’s health was now greatly impaired by the severity of his confinement, and he was seized with a fever, during which his life was despaired of by all in the ship. But even in this state his fortitude of mind remained unsubdued, and he comforted his fellow-prisoners with hopes of release.

To their anxious desponding inquiries (natural to men in their situation), “if he thought they would ever obtain their liberty,” his uniform answer was, “God will deliver us to his glory, even in this life.” While they lay on the coast between Dundee and St. Andrews, Mr. (afterwards Sir) James Balfour, who was confined in the same ship with him, pointed to the spires of St. Andrews, and asked him if he knew the place.

“Yes,” replied the sickly and emaciated captive, “I know it well; for I see the steeple of that place where God first opened my mouth in public to his glory; and I am fully persuaded, how weak soever I now appear, that I shall not depart this life, till that my tongue shall glorify his godly name in the same place.” This striking reply Sir James repeated in the presence of a number of witnesses many years before Knox returned to Scotland, and when there was very little prospect of his words being verified. We must not, however, think that he possessed this tranquillity and elevation of mind during the whole period of his imprisonment. When first thrown into fetters, insulted by his enemies, and deprived of all prospect of release, he was not a stranger to the anguish of despondency, so pathetically described by the royal psalmist of Israel. He felt that conflict in his spirit, with which all good men are acquainted, and which becomes peculiarly sharp when aggravated by corporal affliction; but having had recourse to prayer, the never-failing refuge of the oppressed, he was relieved from all his fears, and reposing upon the promise and the providence of the God whom he served, he attained to “the confidence and rejoicing of hope.” Those who wish for a more particular account of the state of his mind at this time, will find it in the notes, extracted from a rare work which he composed on prayer, and the chief materials of which were suggested by his own experience.

When free from fever, he relieved the tedious hours of captivity, by committing to writing a confession of his faith, containing the substance of what he had taught at St. Andrews, with a particular account of the disputation which he had maintained in St. Leonard’s Yards. This he found means to convey to his religious acquaintances in Scotland, accompanied with an earnest exhortation to persevere in the faith which they had professed, whatever persecutions they might suffer for its sake. To this confession I find him referring in the defence which he afterwards made before the Bishop of Durham. “Let no man think, that because I am in the realm of England, therefore so boldly I speak. No : God hath taken that suspicion from me. For the body lying in most painful bands, in the midst of cruel tyrants, his mercy and goodness provided that the hand should write and bear witness to the confession of the heart, more abundantly than ever yet the tongue spake.”

Notwithstanding the rigor of their confinement, the prisoners who were separated found opportunities of occasionally corresponding with one another. Henry Balnaves of Halhill had composed, in his prison, a treatise on Justification, and the Works and Conversation of a Justified Man. This having been conveyed to Knox, probably after his return from the coast of Scotland, he was so much pleased with the work, that he divided it into chapters, and added some marginal notes, and a concise epitome of its contents; to the whole he prefixed a recommendatory dedication, intending that it should be published for the use of his brethren in Scotland, as soon as an opportunity offered. The reader will not, I am persuaded, be displeased to have some extracts from this dedication, which represent, more forcibly than any description of mine can do, the pious and heroic spirit which animated the Reformer, when “his feet lay in irons;” and I shall quote more freely, as the book is rare.

It is thus inscribed: “John Knox, the bound servant of Jesus Christ, unto his best beloved brethren of the congregation of the castle of St. Andrews, and to all professors of Christ’s true evangel, desireth grace, mercy, and peace, from God the Father, with perpetual consolation of the Holy Spirit.” After mentioning a number of instances in which the name of God had been magnified, and the interests of religion advanced, by the exile of those who were driven from their native countries by tyranny, as in the examples of Joseph, Moses, Daniel, and the primitive Christians, he goes on thus: “Which thing shall openly declare this godly work subsequent. The counsel of Satan in the persecution of us, first, was to stop the wholesome wind of Christ’s evangel to blow upon the parts where we converse and dwell; and, secondly, so to oppress ourselves by corporal affliction and worldly calamities, that no place should we find to godly study. But by the great mercy and infinite goodness of God our Father, shall these his counsels be frustrate and vain. For, in despite of him and all his wicked members, shall yet that same word (O Lord, this I speak, confiding in thy holy promise) openly be proclaimed in that same country. And how that our merciful Father, amongst these tempestuous storms, byt all men’s expectation, hath provided some rest for us, this present work shall testify, which was sent to me in Roane, lying in irons, and sore troubled by corporal infirmity, in a galley named Nostre Dame, by an honorable brother, Mr. Henry Balnaves of Halhill, for the present held as prisoner (though unjustly) in the old palace of Roane, which work after I had once and again read, to the great comfort and consolation of my spirit, by counsel and advice of the foresaid noble and faithful man, author of the said work, I thought expedient it should be digested in chapters, &c. Which thing I have done as imbecility of ingine and incommodity of place would permit; not so much to illustrate the work (which in the self is godly and perfect) as, together with the foresaid noble man and faithful brother, to give my confession of the article of justification therein contained.

And I beseech you, beloved brethren, earnestly to consider, if we deny any thing presently (or yet conceal and hide) which any time before we professed in that article. And now we have not the castle of St. Andrews to be our defence, as some of our enemies falsely accused us, saying, If we wanted our walls, we would not speak so boldly. But blessed be that Lord whose infinite goodness and wisdom hath taken from us the occasion of that slander, and hath shown unto us, that the serpent hath power only to sting the heel, that is, to molest and trouble the flesh, but not to move the spirit from constant adftering to Christ Jesus, nor public professing of his true word. O blessed be Thou, Eternal Father! which, by thy only mercy, hast preserved ut to this day, and provided that the confession of our faith (which ever we desired all men to have known) should, by this treatise, come plainly to light. Continue, 0 Lord! and grant unto us, that, as now with pen and ink, so shortly we may confess with voice and tongue the same before thy congregation; upon whom, look, O Lord God! with the eyes of thy mercy, and suffer no more darkness to prevail. I pray you, pardon me, beloved brethren, that on this manner I digress: vehemency of spirit (the Lord knoweth I lie not) compelleth me thereto.”

The prisoners in Mont St. Michel consulted Knox as to the lawfulness of attempting to escape by breaking their prison, which was opposed by some of them, lest their escape should subject their brethren who remained in confinement to more severe treatment. He returned for answer, that such fears were not a sufficient reason for relinquishing the design, and that they might, with a safe conscience, effect their escape, provided it could be done “without the blood of any shed or spilt; but to shed any man’s blood for their freedom, he would never consent.” The attempt was accordingly made by them, and successfully executed, “without harm done to the person of any, and without touching any thing that appertained to the king, the captain, or the house.”

At length, after enduring a tedious and severe imprisonment of nineteen months, Knox obtained his liberty. This happened in the month of February 1549, according to the modern computation. By what means his liberation was procured I cannot certainly determine. One account says, that the galley in which he was confined was taken in the Channel by the English. According to another account, he was liberated by order of the King of France, because it appeared, on examination, that he was not concerned in the murder of Cardinal Beaton, nor accessory to other crimes committed by those who held the castle of St. Andrews. In the opinion of others, his liberty was purchased by his acquaintances, who fondly cherished the hope that he was destined to accomplish some great achievements, and were anxious, by their interposition in his behalf, to be instrumental in promoting the designs of Providence. It is more probable, however, that he owed his deliverance to the comparative indifference with which he and his brethren were now regarded by the French court, who, having procured the consent of the Parliament of Scotland to the marriage of Queen Mary to the dauphin, and obtained possession of her person, felt no longer any inclination to revenge the quarrels of the Scottish clergy.