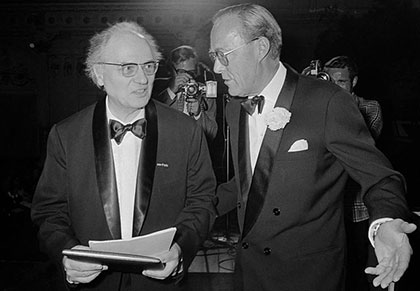

[ABOVE—Prince Bernhard awarded Erasmus Prize to Olivier Messiaen in Concertgebouw Amsterdam, photo by Rob Mieremet / Anefo; (Edited version of Nationaal Archief) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons File:Olivier Messiaen (1971).jpg]

Olivier Messiaen is an example of a prisoner who focused his attention not on his grim outward circumstances but on his inner artistic vision. He was staunchly Catholic, and, with the exception of some months during World War II, was organist of the Church of La Trinité in Paris from 1931 until his death in 1992.

Sandfloor Cathedral. In this unusual video journey, viewers become deep sea divers from the comfort of their own living rooms as we explore ocean depths, sea life, and the extraordinary interplay of motion, color and aquatic creatures. All of this is accompanied by the original and award-winning music version of Lee Johnson’s Symphony No. 5, “Sandfloor Cathedral,” which like Messiaen’s music goes to nature for inspiration.

Like most other able-bodied men, he was conscripted to fight the Germans during World War II, but because of his poor eyesight he served as a medical auxiliary rather than as an infantryman. Captured in May, 1940, Olivier Messiaen was transported to Stalag VIII-A where he spent about a year until his release. On the way to Stalag VIII-A, he showed some musical sketches to a fellow prisoner, the Jewish clarinetist Henri Akoka. Akoka was interested and Messiaen developed these ideas for him. After he arrived in the camp, Messiaen discovered a violinist and a cellist among his fellow prisoners: Jean le Boulaire and Étienne Pasquier. Building on earlier ideas and the piece he had done for Akoka, Messiaen developed an eight-movement quartet for piano, clarinet, violin, and cello.

The quartet dispensed with traditional timing, and demanded difficult techniques from the players. Akoka, for example, was asked to hold notes longer than was humanly possible. In the quartet, Messiaen also indulged his fascination with bird songs, transcribing and adapting several for the first movement. He described the movement with these words,

“Between three and four in the morning, the awakening of birds: a solo blackbird or nightingale improvises, surrounded by a shimmer of sound, by a halo of trills lost very high in the trees. Transpose this onto a religious plane and you have the harmonious silence of Heaven.”

Movement V (my favorite) is titled “Praise to the Eternity of Jesus” and the final movement “Praise to the Immortality of Jesus.”

Messiaen took as his inspiration words from the tenth chapter of the Book of Revelation:

“And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire…and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth.… And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, and swore by him that liveth for ever and ever…that there should be time no longer: But in the days of the voice of the seventh angel, when he shall begin to sound, the mystery of God should be finished…”

Messiaen named the work For the End of Time—a deliberate pun. Not only did it refer to the end of time in our physical universe (“there should be time no longer”) but to the abolition of traditional time-signatures throughout the piece.

A German officer named Brüll who loved art music allowed Messiaen time to compose and to practice the work with his friends. Messiaen himself played the camp’s beat up piano. They premiered the difficult, fifty-minute piece, on January 15, 1941, in front of about 400 prisoners—all who could squeeze into the barracks hall. The weather was bitterly cold, and the hall poorly heated. Indeed, much of its warmth was derived from the bodies crowded within it. According to Messiaen, despite the adverse conditions and the unlikely audience, his music was never listened to with such rapt attention and comprehension.

For the End of Time remains a 20th-century masterpiece. Although it is extremely difficult to play, many recordings have been made of it. View Messiaen’s Quartet on YouTube

The spiritual dimension of Messiaen’s work was not without effect, either. The violinist, Le Bouilaire described himself as an unbeliever; yet Messiaen’s music, his love of birdsong, his kindness, and his unwavering faith combined to force this atheist to consider the possibility of God, and brought him consolation. “But all of a sudden Messiaen would begin to sing. That’s what made me really stumble over the question of the divine.” Thus, as a prisoner, both by his art and his conduct, Messaien made a mark for the kingdom of Christ.