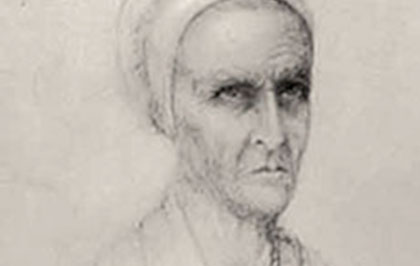

[ABOVE—Marie Durand’s face was pinched with suffering, by Société de l’Histoire du Protestantisme français [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons File:MarieDurand.jpg]

Imagine being confined in a circular stone prison with few necessities and no comforts. What little light and air you get comes through a six foot circular hole far above your head, through which rain and snow also descend in their season. You receive your food and water through a similar hole in the floor. Smoke from a fire below belches upward through the opening and you toss your refuse down it. Such was the home of Marie Durand and about forty Huguenot women for decades.

Great Women In Christian History. Christian history abounds with the names of other women who had a tremendous influence on the spread of Christianity and on the tone of civilization. Great Women in Christian History tells the stories of 37 of these notable women — women who have served God’s kingdom as missionaries, martyrs, educators, charitable workers, wives, mother and instruments of justice.

Scratched on the rim of the refuse hole of the Tower of Constance is the French word “Resistez!” Resist! Tradition ascribes this slogan to Marie Durand because she was the most famous inmate of the tower when the slogan appeared.

Merely because her brother was a Huguenot pastor who held Protestant services in his home, she was ripped from her family as a teen—torn from the arms of the husband she had just wed—and flung into prison.

Young as she was, she became the light of the place, and because of her education, was able to act as an agent for the women. And for 38 long years she led the other women in song and prayer. With them she endured the cold of winter and the heat of summer. Letter after letter she wrote, trying to better their condition, and prevailed on the authorities to allow them a book of psalms. The women were allowed to knit, and, curiously, Marie was allowed to write to her outlawed pastor, Paul Rabaut.

If ever there was a prisoner unjustly imprisoned, it would seem to be Marie Durand. But sad as her story was, there was a sadder. One of the inmates was an eight year old girl, imprisoned for forty years because her mother had taken her to a Protestant service.

How bad was their incarceration? Here is an account by the aide-de-camp of Prince de Beauveau. Over the protests of King Louis XV, the Prince indignantly released the captives shartly after taking charge of the Languedoc district in which they were imprisoned.

We found at the entrance to the tower an assiduous doorkeeper. He led us upward by dark and torturous stairways, and at length opened for us with great noise a frightful door, over which one almost read the inscription of Dante, “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.” I have no colors with which to paint the horror of a spectacle to which our eyes were so little used, a picture hideous and at the same time touching, a picture of which the interest was only increased by disgust. We saw a great circular apartment, destitute of air and of daylight, and in that great room forty women languishing in misery, infection, and tears. The governor could scarcely contain his emotion, and for the first time, without doubt, those unfortunate women perceived compassion on a human face. I see them still, at our sudden entrance, like an apparition, all falling at his feet, deluging them with their tears, striving to find words, but able only to express themselves in sobs; then, when emboldened by our sympathy, recounting their common griefs. Alas! Their only crime was that of having been instructed in the same religion as that of Henry IV. The youngest of those martyrs was more than fifty years old. She was only eight years old when she was arrested, because she had gone to a preaching service with her mother, and the punishment was lasting still.

“You are free!” were the words uttered by a loud voice, but a voice trembling with pity, and I was proud that it was the voice of the governor. But, as the most of them were entirely without resources, without experience, without family or friends, these poor captives, astonished by liberty, ran the risk of new misfortunes, and their deliverer at once made provision for their needs.

Marie may have scratched “resist” on the pit, but what she wrote on hearts will last an eternity. She was released as an old woman and cared for by kindly Walloons. Her family home became a Huguenot monument, a testimony of religious steadfastness in the face of unjust ecclesiastical and royal oppression. Here are excerpts from two of Marie’s letters to Pastor Rabaut.

A Letter of 1762.

I have the honor to inform you that many of my fellow-prisoners were obliged to run in debt in their illnesses last year, and that I was in the same condition. I must tell you in truth that then I owed twenty-five crowns. Now I do not owe so much, having paid fifty livres. But God knows what I have gone through for it! All the summer I have done without a gown, apron, shoes, and other necessary things; provided only I can get out of debt before leaving this cruel prison I shall be satisfied.

A letter of 1764.

Sir, very dear and much honored Pastor, it is to you we have recourse; it is to your pastoral kindness I apply for a remedy to prevent an infection which is likely to spread among us…In the name of the divine mercy, use every possible effort to rescue us from our frightful sepulchre. We are in urgent need of all the help you can give…[she continues with kind expressions toward him and his family] Burn my letter if you please. Have the goodness to pray for us, particularly for our sick; the health of nearly all of us is much affected.