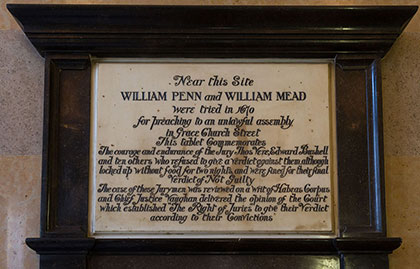

[ABOVE—William Penn and William Mead plaque at the Old Bailey. Paul Clarke [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons File:William Penn & William Mead – plaque – 01.jpg]

In the United States prisoners enjoy the right to trial by a jury if they choose it. On paper, William Penn also had that right. In actuality, the Stuart government bullied or tampered with juries to force them to return verdicts pleasing to its officials. When Penn and William Mead were arrested in 1670 for preaching, the mayor and magistrate attempted to coerce their jury. The excerpt below recounts the whole shameful episode. In the end, Penn and Mead prevailed on the sturdy jury to stand with them, and a higher court ruled that magistrates might no longer coerce juries. Penn had helped establish a major civil right for accused prisoners in English-speaking lands.

Quakers—That of God in Everyone.

Though many are familiar with the Quaker names such as William Penn, Susan B. Anthony, Daniel Boone, and Johns Hopkins, lesser-known Quakers also impacted society in significant ways. These are untold stories Friends who profoundly influenced the course of American history by seeing that of God in everyone.

At worst, William Penn’s “crimes” were misdemeanors. He preached in public when it was against the law to do so. He refused to remove his hat as a sign of respect to any man. He published a book without obtaining a license—a rule generally neglected at that time by authors and publishers, and only selectively enforced by the government. Nonetheless, he paid the full penalty for his civil disobedience, often going to prison.

His times in prison resulted in more than civil rights. During a 1669 incarceration in the Tower of London on a charge of blasphemy (his ideas on the Trinity did not match those of the Church of England), Penn committed another misdemeanor by obtaining paper and ink to write his most famous book No Cross, No Crown. That winter was particularly cold and Penn was subjected to its rigors without a fire. He suffered the cold and ate the common prison fare, which was none too good. But once again he proved that incarceration cannot prevent a man from doing good if he chooses.

A Selection from Samuel M. Janney’s Life of William Penn

In this year [1670] was renewed the noted “Conventicle Act,” which was professedly against “seditious conventicles,” but really intended to suppress all religious meetings, conducted “in any other manner than according to the liturgy and practice of the church of England” It had been first suggested by some of the bishops. The chaplain of the Archbishop of Canterbury had previously printed a discourse against toleration, in which he asserted as a main principle, that, “it would be less injurious to the government to dispense with profane and loose persons, than to allow toleration to religious dissenters”

“This act,” says Thomas Ellwood, “broke down and overran the bounds and banks anciently set for the security of Englishmen’s lives, liberties, and properties; namely, trials by jury, instead thereof, authorizing justices of the peace (and that too, privately, out of sessions) to convict, fine, and by their warrants, distrain upon offenders against it, directly contrary to the Great Charter” There is a remarkable clause in this act, which shows the bitter spirit of persecution then existing in the House of Commons. It provides, “that in case of any doubt arising about the interpretation of it, the act shall be construed most largely and beneficially for the suppression of Conventicles,” thus violating one of the plainest maxims of civil policy, which requires that in criminal prosecutions, the prisoner should always have the advantage of such doubts.

The chief burden of this persecuting statute fell upon Friends [Quakers], for it was their practice to keep up their meetings for divine worship at stated times and places; as though no such law existed, for they held that no human authority could exempt them from openly avowing their allegiance to God by that mode of worship, to which they believed that he had called them; whereas, many others among the dissenters, stooped for the storm to pass over them, by changing the places of their meetings, and holding them at unusual times.

It was not long before Penn was made to feel the force of this arbitrary law, for on going to the meeting at Grace-church street, he found the house guarded by a band of soldiers. He and other Friends not being permitted to enter, gathered around the doors, where, after standing some time in silence, he felt it his duty to preach, but had not proceeded far, when he and another of the society, William Mead, were arrested by the constables, who produced warrants from Sir Samuel Starling the Mayor of London, dated August the 14th, 1670.

They were conducted by the officers to a place of confinement in Newgate market, as related in the following letter.

WILLIAM PENN TO HIS FATHER.

“Second day morning, 15th of 6th mo. (August) 1070.

“My Dear Father:

“This comes by the hand of one who can best allay the trouble it brings. As true as ever Paul said, that such as live godly in Christ Jesus, shall suffer persecution, so for no other reason am I at present a sufferer. Yesterday I was taken by a band of soldiers, with one Capt. Mead, a linen draper, and in the evening carried before the Mayor; he proceeded against me according to the ancient law; he told me I should have my hat pulled off, for all I was Admiral Penn’s son. I told him that I desired to be in common with others, and sought no refuge from the common usage. He answered, it had been no matter if thou hadst been a commander twenty years ago. I discoursed with him about the hat; he avoided it, and because I did not readily answer him my name, William, when he asked me in order to a mittimus, he bid his clerk write one for Bridewell, and there would he see me whipped himself, for all I was Penn’s son, that starved the seamen. Indeed these words grieved me, as well as that it manifested his great weakness and malice to the whole company, that were about one hundred people. I told him I could very well bear his severe expressions to me concerning myself, but was sorry to hear him speak those abuses of my father, that was not present, at which the assembly seemed to murmur. In short, he committed that person with me as rioters; and at present we are at the sign of the Black Dog, in Newgate market.

“And now, dear father, be not displeased nor grieved. What if this be designed of the Lord for an exercise of our patience? I am sure it hath wonderfully laid bare the nakedness of the Mayor. Several Independents were taken from Sir J. Dethicks, and Baptists elsewhere. It is the effect of a present commotion in the spirits of some, which the Lord God will rebuke; and I doubt not but I may be at liberty in a day or two, to see thee. I am very well, and have no trouble upon my spirits, besides my absence from thee, especially at this juncture, but otherwise I can say, I was never better; and what they have to charge me with is harmless. Well, eternity, which is at the door, (for he that shall come will come, and will not terry,) that shall make amends for all. The Lord God everlasting consolate and support thee by his holy power, and preserve to his eternal rest and glory. Amen.

“Thy faithful and obedient son,

“WILLIAM PENN.

“My duty to my mother. For my dear father, Sir William Penn”

The trial, as related in the published works of Penn, is deeply interesting, and resulting as it did, in the greater security and more firm establishment of civil liberty in England, is deemed worthy of insertion here.

There being present on the Bench as Justices:

Saml. Starling, Mayor, John Robinson, Alderman; John Howell, Recorder Joseph Shelden “ Thos. Bludworth, Alderman Richard Brown, sheriff Wm. Peak, “ John Smith, “ Richard Ford, “ James Edwards, “ The citizens of London that were summoned for jurors, appearing, were empanneled, viz:

Clerk. Call over the Jury.

Crier. Oyez, Thomas Veer, Ed. Bushell, John Hammond, Charles Wilson, Gregory Walklet, John Brightman, Wm. Plumstead, Henry Henley, James Damask, Henry Michel, Wm. Lever, John Baily.

THE FORM OF THE OATH.

You shall well and truly try, and true deliverance make between our Sovereign Lord the King, and the prisoners at the bar, according to your evidence; so help you God.THE INDICTMENT.

That William Penn, gent., and William Mead, late of London, linen-draper, with divers other persons, to the jurors unknown, to the number of three hundred, the 15th day of August, in the 22nd year of the King, about eleven of the clock in the forenoon, the same day with force and arms, &c., in the Parish of St. Bennet, Grace-Church, in Bridge-Ward, London, in the street called Grace-Church Street, unlawfully and tumultuously did assemble and congregate themselves together, to the disturbance of the peace of the said Lord the King; and the aforesaid William Penn and William Mead, together with other persons, to the jurors aforesaid unknown, then and there so assemble and congregate together; the aforesaid William Penn, by agreement between him and William Mead, before made, and by abetment of the aforesaid Wm. Mead, then and there, in the open street, did take upon himself to preach and speak, and then, and there, did preach and speak, unto the aforesaid Wm. Mead, and other persons there, in the street aforesaid, being assembled and congregated together, by reason whereof a great concourse and tumult of people in the street aforesaid, then and there a long time did remain and continue, in contempt of the said Lord the King, and of his law; to the great disturbance of his peace, to the great terror and disturbance of many of his liege people and subjects, to the ill example of all others in the like case offenders, and against the peace of the said Lord the King, his crown and dignity.What say you, Wm. Penn and Wm. Mead, are you guilty, as you stand indicted, in the manner and form as aforesaid, or not guilty?

Penn. It is impossible that we should be able to remember the indictment verbatim, and therefore we desire a copy of it, as is customary on the like occasions.

Reed. You must first plead to the indictment, before you have a copy of it.

Penn. I am unacquainted with the formality of the law, and, therefore, before I shall answer directly, I request two things of the court, First, That no advantage may be taken against me, nor I deprived any benefit which I might otherwise have received. Secondly, That you will promise me a fair hearing and liberty of making my defense.

Court. No advantage shall be taken against you, you shall have liberty, you shall be heard.

Penn. Then I plead not guilty in manner and form.

Clerk. What sayst thou, Wm. Mead; art thou guilty in manner and form, as thou stand’st indicted, or not guilty?

Mead. I shall desire the same liberty as granted to Penn.

Court. You shall have it.

Mead. Then I plead not guilty in manner and form.

The Court adjourned until afternoon.

Crier. 0yez,etc.

Clerk. Bring Wm. Penn and Wm. Mead to the bar.

Observer. The said prisoners were brought, but were set aside, and other business prosecuted; where we cannot choose but observe, that it was the constant and unkind practice of the court to the prisoners, to make them wait upon the trials of felons and murderers, thereby designing, in all probability, both to affront and tire them.

After five hours’ attendance the court broke up, and adjourned to the third instant.

The third of September, 1670, the court sat.

Crier. Oyez, etc.

Mayor. Sirrah, who bid you put off their hats? Put on their hats again.

Observer. Whereupon one of the officers, putting the prisoners’ hats upon their heads, (pursuant to the order of the Court), brought them to the bar.

Recorder. Do you know where you are?

Penn. Yes.

Reed. Do you know it is the King’s court?

Penn. I know it to be a court, and I suppose it to be the King’s court.

Reed. Do you know there is respect due to the court?

Penn. Yes.

Reed. Why do you not pay it then?

Penn. I do So.

Reed. Why do you not put off your hat then?

Penn. Because I do not believe that to be respect.

Reed. Well, the court sets forty marks a-piece upon your heads, as a fine, for your contempt of the court.

Penn. I desire it may be observed, that we came into the court with our hats off, (that is, taken off), and if they have been put on since, it was by order from the bench; and therefore, not we, but the bench should be fined.

Mead. I have a question to ask the Recorder; am I fined also?

Reed. Yes.

Mead. I desire the jury and all tbe people to take notice of this injustice of the Recorder, who spake not to me to pull off my hat, and yet hath he put a fine upon my head. 0, fear the Lord and dread his power, and yield to the guidance of this Holy Spirit; for He is not far from every one of you.

The Jury sworn again.

Observer. J. Robinson, Lieutenant of the Tower, disingenuously objected against Edward Bushell, as if he had not kissed the book, and therefore would have him sworn again: though indeed it was on purpose to have made use of his tenderness of conscience, in avoiding reiterated oaths, to have put him, by his being a juryman, apprehending him to be a person not fit to answer their arbitrary ends.

The clerk read the indictment as aforesaid.

Clerk. Crier, call James Cook into the court, give him his oath.

Clerk. James Cook, lay your hand upon the book: “The evidence you shall give the court betwixt our Sovereign the King and the prisoners at the bar, shall be the truth, and the whole truth, and nothing but the truth; so help you God”

Cook. I was sent for from the exchange, to go and disperse a meeting in Gracious street, where I saw Mr. Penn speaking to the people, but I eould not hear what he said, because of the noise; I endeavored to make way to take him, but I could not get to him for the crowd of people; upon which Captain Mead came to me, about the kennel of the street, and desired me to let him go on; for when he had done, he would bring Mr. Penn to me.

Court. What number do you think might be there?

Cook. About three or four hundred people.

Court. Call Richard Reed, give him his oath.

Reed being sworn, was asked, What do you know concerning the prisoners at the bar?

Reed. My Lord, I went to Gracious street, where I found a great crowd of people, and I heard Mr. Penn preach to them, and I saw Capt. Mead speaking to Lieutenant Cook, but what he said I could not tell.

Mead. What did Wm. Penn say?

Reed. There was such a great noise, that I could not tell what he said.

Mead. Jury, observe this evidence: he saith he heard him preach, and yet saith, he doth not know what he said.

Jury, take notice, he swears now a clean contrary thing, to what he swore before the Mayor, when we were committed: for now he swears that he saw me in Gracious streets, and yet he swore before the Mayor, when I was committed, that he did not see me there. I appeal to the Mayor himself, if this be not true: but no answer was given.

Court. What number do you think might be there?

Reed. About four or five hundred.

Penn. I desire to know of him what day it was?

Reed. The 14th day of August.

Penn. Did he speak to me, or let me know he was there; for I am very sure I never saw him.

Clerk. Crier, call into the court.

Court. Give him his oath.

My Lord, I saw a great number of people, and Mr. Penn, I suppose, was speaking; I saw him make a motion with his hands, and heard some noise, but could not understand what he said; but for Capt. Mead, I did not see him there.

Reed. What say you, Mr. Mead? Were you there?

Mead. It is a maxim in your own law, nemo tenetur accusare seipsum, which, if it be not true Latin, I am sure that it is true English, that no man is bound to accuse himself. And why dost thou offer to ensnare me with such a question? Doth not this shew thy malice? Is this like unto a judge, that ought to be counsel for the prisoner at the bar?

Reed. Sir, hold your tongue, I did not go about to ensnare you.

Penn. I desire we may come more close to the point, and that silence be commanded in the court.

Crier. 0yez, all manner of persons keep silence, upon pain of imprisonment—silence in the court.

Penn. We confess ourselves to be so far from recanting, or declining to vindicate the assemblage of ourselves to preach, pray, or worship the eternal, holy, just God, that we declare to all the world, that we do believe it to be our indispensable duty, to meet incessantly upon so good an account; nor shall all the powers upon earth be able to divert us from reverencing and adoring our God, who made us.

Brown. You are not here for worshipping God, but for breaking the law; you do yourselves a great deal of wrong in going on in that discourse.

Penn. I affirm I have broken no law, nor am I guilty of, the indictment that is laid to my charge: and to the end, the bench, the jury, and myself, with those that hear us, may have a more direct understanding of this procedure, I desire you would let me know by what law it is you prosecute me, and upon what law you ground my indictment.

Reed. Upon the common law.

Penn. What is that common law?

Reed. You must not think that I am able to run up so many years, and over so many adjudged cases, which we call common law, to answer your curiosity.

Penn. This answer, I am sure, is very short of my question; for if it be common, it should not be so hard to produce.

Reed. Sir, will you plead to your indictment?

Penn. Shall I plead to an indictment that hath no foundation in law? If it contain that law you say I have broken, why should you decline to produce that law, since it will be impossible for the jury to determine or agree to bring in their verdict, who hath not the law produced, by which they should measure the truth of this indictment, and the guilt or contrary of my fact.

Reed. You are a saucy fellow; speak to the indictment.

Penn. I say it is my place to speak to matter of law; I am arraigned a prisoner; my liberty, which is next to life itself, is now concerned; you are many mouths and ears against me, and if I must not be allowed to make the best of my case, it is hard: I say again, unless you show me, and the people, the law you ground your indictment upon, I shall take it for granted, your proceedings are merely arbitrary.

Observer. (At this time several upon the bench urged hard upon the prisoner, to bear him down.)

Reed. The question is, whether you are guilty of this indictment?

Penn. The question is not whether I am guilty of this indictment, but whether this indictment be legal. It is too general and imperfect an answer, to say it is the common law, unless we knew both where and what it is; for where there is no law, there is no transgression, and that law which is not in being, is so far from being common, that it is no law at all.

Reed. You are an impertinent fellow; will you teach the Court what law is? It’s lex non scripta, that which many have studied thirty or forty years to know, and would you have me tell you in a moment?

Penn. Certainly, if the common law be so hard to be understood, it’s far from being very common; but if the Lord Cook in his Institutes be (if any consideration, he tells us, that common law is common right; and that common right is the great charter privileges, confirmed 9 Hen. III. 29; 25 Edw. I. 1; 2 Edw. III. 8; Cook’s Insts. 2, p. 56.

Reed. Sir, you are a troublesome fellow, and it is not for the honor of the court to suffer you to go on.

Penn. I have asked but one question, and you have not answered me; though the rights and privileges of every Englishman be concerned in it.

Reed. If I should suffer you to ask questions till to-morrow morning, you would be never the wiser.

Penn. That’s according as the answers are.

Reed. Sir, we must not stand to hear you talk all night.

Penn. I design no affront to the court, but to be heard in my just plea: and I may plainly tell you, that if you will deny me the oyer of that law, which you suggest I have broken, you do at once deny me an acknowledged right, and evidence to the world your resolution to sacrifice the privileges of Englishmen to your sinister and arbitrary designs.

Reed. Take him away; my Lord, if you take not some course with this pestilent fellow, to stop his mouth, we shall not be able to do any thing to-night.

Mayor. Take him away, take him away! turn him into the Bale-dock.

Penn. These are but so many vain exclamations; is this justice or true judgment? Must I, therefore, be taken away because I plead for the fundamental laws of England? However, this I leave upon your consciences, who are of the jury (and my sole judges), that if these ancient fundamental laws, which relate to liberty and property (and are not limited to particular persuasions in matters of religion), must not be indispensably maintained and observed, who can say he has a right to the coat upon his back? Certainly, our liberties are openly to be invaded; our wives to be ravished; our children slaved; our families mined; and our estates led away in triumph by every sturdy beggar and malicious informer, but our (pretended) forfeits for conscience-sake; the Lord of heaven and earth will be judge between us in this matter.

Reed. Be silent there.

Penn. I am not to be silent in a case wherein I am so much concerned; and not only myself, but many ten thousand families besides.

Observer. They having rudely haled him in the Bale-dock, Wm. Mead they left in the court, who spoke as follows:

Mead. You men of the jury, here I do now stand to answer to an indictment against me, which is a bundle of stuff full of lies and falsehoods; for therein I am accused, that I met, vi and armis, illicite and tumultuouse. Time was when I had freedom to use a carnal weapon, and then I thought I feared no man; but now I fear the living God, and dare not make use thereof, nor hurt any man; nor do I know I demeaned myself as a tumultuous person. I say I am a peaceable man, therefore it is a very proper question what Wm. Penn demanded in this case, an oyer of the law on which our indictment is grounded.

Reed. I have made answer to that already.

Mead, turning his-face to the jury, said, “you men of the jury, who are my judges, if the Recorder will not tell you what makes a riot, a rout or an unlawful assembly, Cook, (he that once they called) the Lord Cook, tells us what makes a riot, a rout, and an unlawful assembly, a riot is, when three or more are met together to beat a man, or to enter forcibly into another man’s land, to cut down his grass, his wood, or break down his pales.”

Observer. Here the Recorder interrupted him, and said, I thank you, sir, that you will tell me what the law is? scornfully pulling off his hat.

Mead. Thou mays’t put on thy hat, I have never a fee for thee now.

Brown. He talks at random, one while an Independent, another while some other religion, and now a Quaker, and next a Papist.

Mead. Turpe est doctori cum culpa redarguit ipsum.

Mayor. You deserve to have your tongue cut out.

Reed. If you discourse on this manner, I shall take occasion against you.

Mead. Thou didst promise me I should have fair liberty to be heard. Why may I not have the privileges of an Englishman? I am an Englishman, and you might be ashamed of this dealing.

Reed. I look upon you to be an enemy to the laws of England, which ought to be observed and kept, nor are you worthy of such privileges as others have.

Mead. The Lord is judge between me and thee in this matter.

Observer. Upon which they took him away into the Bale-dock, and the Recorder proceeded to give the jury their charge, as follows:

Reed. You have heard what the indictment is; it is for preaching to the people, and drawing a tumultuous company after them; and Mr. Penn was speaking. If they should not be disturbed, you see they will go on; there are three or four witnesses that have proved this, that he did preach there, that Mr. Mead did allow of it; after this you have heard, by substantial witnesses, what is said against them. Now we are upon the matter of fact, which you are to keep to and observe as what hath been fully sworn, at your peril.

Observer. The prisoners were put out of the court into the Bale-dock, and the charge given to the jury in their absence, at which Wm. Penn, with a very raised voice, it being a considerable distance from the bench, spake,

Penn. I appeal to the jury, who are my judges, and this great assembly, whether the proceedings of the court are not most arbitrary, and void of all law, in offering to give the jury their charge in the absence of the prisoners; I say it is directly opposite to, and destructive of the undoubted right of every English prisoner, as Cook in the 2 Inst. 29, on the chapter of Magna Charter, speaks.

Observer. The Recorder being thus unexpectedly lashed for his extrajudicial procedure, said, with an enraged smile.

Reed. Why ye are present, you do hear: do you not?

Penn. No thanks to the court, that commanded me into the Bale- dock; and you of the jury take notice, that I have not been heard, neither can you legally depart the court, before I have been fully heard, having at least ten or twelve material points to offer, in order to invalidate their indictment.

Reed. Pull that fellow down; pull him down.

Mead. Are these according to the rights and privileges of Englishmen, that we should not be heard, but turned into the Bale-dock for making our defence, and the jury to have their charge given them in our absence? I say these are barbarous and unjust proceedings.

Reed. Take them away into the hole; to hear them talk all night, as they would, I think doth not become the honor of the court; and I think you, (i. e. the jury,) yourselves, would be tired out, and not have patience to hear them.

Observer. The jury were commanded up to agree upon their verdict, the prisoners remaining in the stinking hole; after an hour and half’s time, eight came down agreed, but four remained above; the court sent an officer for them, and they accordingly came down. The bench used many unworthy threats to the four that dissented; and the Recorder, addressing himself to Bushell, said,“Sir, you are the cause of this disturbance, and manifestly shew yourself an abettor of faction. I shall set a mark upon you, sir”

J. Robinson. Mr. Bushell, I have known you near this fourteen years; you have thrust yourself upon this jury, because you think there is some service for you; I tell you, you deserve to be indicted more than any man that hath been brought to the bar this day.

Bushell. No, Sir John, there were threescore before me, and I would willingly have got off, but could not.

Bludworth. I said, when I saw Mr. Bushell, what I see is come to pass; for I knew he would never yield. Mr. Bushell, we know what you are.

Mayor. Sirrah, you are an impudent fellow, I will put a mark upon you.

Observer. They used much menacing language, and behaved themselves very imperiously to the jury, as persons not more void of justice, than sober education. After this barbarous usage, they sent them to consider of bringing in their verdict, and after some considerable time, they returned to the court. Silence was called for, and the jury called by their names.

Clerk. Are you agreed upon your verdict?

Jury. Yes.

Clerk. Who shall speak for you?

Jury. Our foreman.

Clerk. Look upon the prisoners at the bar. How say you? Is Wm. Ponn guilty of the matter whereof he stands indicted, in manner and form, or not guilty?

Foreman. Guilty of speaking in Gracious street.

Court. Is that all?

Foreman. That is all I have in commission.

Reed. You had as good say nothing.

Mayor. Was it not an unlawful assembly? You mean, he was speaking to a tumult of people there?

Foreman. My Lord, this was all I had in commission.

Observer. Here some of the jury seemed to buckle to the question of the court, upon which Bushell, Hammond, and some others, opposed themselves, and said, they allowed of no such word as an unlawful assembly, in their verdict, at which the Recorder, Mayor, Robinson, and Bludworth, took great occasion to vilify them, with most opprobrious language; and this verdict not serving their turns, the Recorder expressed himself thus:

Reed. The law of England will not allow you to depart, till you have given in your verdict.

Jury. We have given in our verdict, and we can give in no other.

Reed. Gentlemen, you have not given your verdict, and you had as good say nothing; therefore go and consider it once more, that we may make an end of this troublesome business.

Jury. We desire we may have pen, ink, and paper.

Observer. The court adjourns for half an hour; which, being expired, the court returns, and the jury not long after. The prisoners were brought to the bar, and the jurors’ names called over.

Clerk. Are you agreed of your verdict?

Jury. Yes.

Clerk. Who shall speak for you?

Jury. Our foreman.

Clerk. What say you? Look upon the prisoners. Is Wm. Penn guilty in manner and form, as he stands indicted, or not guilty?

Foreman. Here is our verdict; holding forth a piece of paper to the clerk of the peace, which follows:

We, the jurors, hereafter named, do find Wm. Penn to be guilty of speaking or preaching to an assembly, met together in Gracious street, the 14th of August last, 1070, and that Mr. Mead is not guilty of the said indictment.

Foreman, Thomas Veer, Henry Michel, John Bailey, Edw. Bushell, John Brightman, Wm. Lever,

John Hammond, Chas. Milson, Jas. Damask, Henry Uenly, Gregory Walklet, Wm. Plumstcad.Observer. This both Mayor and Recorder resented at so high a rate, that they exceeded the bounds of all reason and civility.

Mayor. What, will you be led by such a silly fellow as Bushell, an impudent, canting fellow? I warrant you, you shall come no more upon juries in haste. You are a foreman indeed, (addressing himself to the foreman), I thought you had understood your place better.

Reed. Gentlemen, you shall not be dismissed till we have a verdict the court will accept; and you shall be locked up without meat, drink, fire, and tobacco. You shall not think thus to abuse the court; we will have a verdict, by the help of God, or you shall starve for it.

Penn. My jury, who are my judges, ought not to be thus menaced; their verdict should be free, and not compelled; the bench ought to wait upon them, but not forestall them; I do desire that justice may be done me, and that the arbitrary resolves of the bench may not be made the measure of my jury’s verdict.

Reed. Stop that prating fellow’s mouth, or put him out of the court.

Mayor. You have heard that he preached; that he gathered a company of tumultuous people; and that they do not only disobey the martial power, but the civil also.

Penn. It is a great mistake, we did not make the tumult, but they that interrupted us. The jury cannot be so ignorant as to think that we met there with a design to disturb the civil peace, since (1st) we were by force of arms kept out of our lawful house, and met as near it in the street as the soldiers would give us leave; and (2nd) because it was no new thing, (nor with the circumstances expressed in the indictment, but what was usual and customary with us,) ’tis very well known that we are a peaceable people, and cannot offer violence to any man.

Observer. The court being ready to break up, and willing to hustle the prisoners to their jail, and the jury to their chamber, Penn spake as follows:

Penn. The agreement of twelve men is a verdict in law, and such a one being given by the jury, I require the clerk of the peace to record it, as he will answer at his peril. And if the jury bring in another verdict contrary to this, I affirm they are perjured men in law; (and looking upon the jury, said): You are Englishmen, mind your privilege; give not away your right.

Bushell, etc. Nor will we ever do it.

Observer. One of the jurymen pleaded indisposition of body, and therefore desired to be dismissed.

Mayor. You are as strong as any of them; starve, then, and hold your principles.

Reed. Gentlemen, you must be content with your hard fate; let your patience overcome it; for the court is resolved to have a verdict, and that before you can be dismissed.

Jury. We are agreed, we are agreed, we are agreed.

Observer. The court swore several persons to keep the jury all night, without meat, drink, fire, or any other accommodation [i.e., restrooms].

Crier. Oyez, etc.

Observer. The court adjourned till seven of the clock next morning (being the 4th inst., vulgarly called Sunday), at which time the prisoners were brought to the bar, the court sat, and the jury called in to bring in their verdict.

Crier. Oyez, etc. Silence in the court, upon pain of imprisonment.

The jury’s names called over.

Clerk. Are you agreed upon your verdict?

Jury. Yes.

Clerk. Who shall speak for you?

Jury. Our foreman.

Clerk. What say you? Look upon the prisoners at the bar. Is William Penn guilty of the matter whereof he stands indicted, in manner and form as aforesaid, or not guilty?

Foreman. William Penn is guilty of speaking in Gracious street.

Mayor. To an unlawful assembly?

Bushell. No, my lord, we give no other verdict than what we gave last night; we have no other verdict to give.

Mayor. You are a factious fellow; I’ll take a course with you.

Bludworth. I knew Mr. Bushell would not yield.

Bushell. Sir Thomas, I have done according to my conscience.

Mayor. That conscience of yours would cut my throat.

Bushell. No, my lord, it never shall.

Mayor. But I will cut yours as soon as I can.

Reed. He has inspired the jury; he has the spirit of divination; methinks I feel him ; I will have a positive verdict, or you shall starve for it.

Penn. I desire to ask the Recorder one question: Do you allow of the verdict given of William Mead?

Reed. It cannot be a verdict, because you are indicted for a conspiracy; and one being found not guilty, and not the other, it could not be a verdict.

Penn. If “not guilty” be not a verdict, then you make of the jury and Magna Charta but a mere nose of wax.

Mead. How? Is not guilty no verdict?

Reed. No, ’tis no verdict.

Penn. I affirm that the consent of a jury is a verdict in law; and if William Mead be not guilty, it consequently follows that I am clear, since you have indicted us of a conspiracy, and I could not possibly conspire alone.

Observer. There were many passages which could not be taken which passed between the jury and the court. The jury went up again, having received a fresh charge from the bench, if possible to extort an unjust verdict.

Crier. Oyez, etc. Silence in the court.

Court. Call over the jury: which was done.

Clerk. What say you? Is William Penn guilty of the matter whereof he stands indicted, in manner and form aforesaid, or not guilty?

Foreman. Guilty of speaking in Gracious street.

Reed. What is this to the purpose? I say I will have a verdict. And (speaking to E. Bushell), said, you are a factious fellow; I will set a mark upon you; and whilst I have anything to do in the city, I will have an eye upon you.

Mayor. Have you no more wit than to be led by such a pitiful fellow? I will cut his nose.

Penn. It is intolerable that my jury should be thus menaced; is this according to the fundamental law? Are not they my proper judges by the Great Charter of England? What hope is there of ever having justice done when juries are threatened and their verdict rejected? I am concerned to speak, and grieved to see such arbitrary proceedings. Did not the Lieutenant of the Tower render one of them worse than a felon? And do you not plainly seem to condemn such for factious fellows who answer not your ends? Unhappy are those juries, who are threatened to be fined, and starved, and ruined, if they give not in their verdict contrary to their consciences.

Reed. My Lord, you must take a course with that same fellow.

Mayor. Stop his mouth; jailor, bring fetters, and stake him to the ground.

Penn. Do your pleasure; I matter not your fetters.

Reed. Till now I never understood the reason of the policy and prudence of the Spaniards, in suffering the Inquisition among them; and certainly it will never be well with us till something like the Spanish Inquisition be in England.

Observer. The jury being required to go together to find another verdict, and steadfastly refusing it, (saying they could give no other verdict than what was already given,) the Recorder, in great passion, was running off the bench, with these words in his mouth: I protest I will sit here no longer to hear these things. At which the Mayor calling, “Stay, stay,” he returned, and directed himself unto the jury, and spake as followeth:

Reed. Gentlemen, we shall not be at this pass always with you. You will find the next session of Parliament there will be a law made that those that will not conform shall not have the protection of the law. Mr. Lee, draw up another verdict that they may bring it in special.

Lee. I cannot tell how to do it.

Jury. We ought not to be returned, having all agreed, and set our hands to the verdict.

Reed. Your verdict is nothing: you play upon the court; I say you shall go together and bring in another verdict, or you shall starve; and I will have you carted about the city, as in Edward the Third’s time.

Foreman. We have given in our verdict and all agree to it, and if we give in another, it will be a force upon us to save our lives.

Mayor. Take them up.

Officer. My Lord, they will not go up.

Observer. The Mayor spoke to the sheriff, and he came off his seat, and said:

Sheriff. Come, gentlemen, you must go up; you see I am commanded to make you go.

Observer. Upon which the jury went up, and several were sworn to keep them without any accommodation, as aforesaid, till they brought in their verdict.

Crier. Oyez, etc. The court adjourns till to-morrow morning at seven of the clock.

Observer. The prisoners were remanded to Newgate, where they remained till next morning, and then were brought into court, which being sat, they proceeded as followeth:

Crier. Oyez, etc. Silence in court upon pain of imprisonment.

Clerk. Set William Penn and William Mead to the bar. Gentlemen of the jury answer to your names: Thos. Veer, Edw. Bushell, John Hammond, Henry Henly, Henry Michel, John Brightman, Chas. Milson, Gregory Walklet, John Baily, Wm. Lever, James Damask, Wm. Plum stead, are you all agreed of your verdict?

Jury. Yes.

Clerk. Who shall speak for you?

Jury. Our foreman.

Clerk. Look upon the prisoners: What say you, is William Penn guilty of the matter whereof he stands indicted, in manner and form, etc, or not guilty?

Foreman. You have there read in writing already our verdict, and our hands subscribed.

Observer. The clerk had the paper, but was stopped by the Recorder from reading it; and he commanded to ask for a positive verdict.

Foreman. If you will not accept of it, I desire to have it back again.

Court. That paper was no verdict, and there shall be no advantage taken against you by it.

Clerk. How say you? Is William Penn guilty, etc, or not guilty?

Foreman. Not guilty.

Clerk. How say you? Is William Mead guilty, etc, or not guilty?

Foreman. Not guilty.

Clerk. Then harken to your verdict: you say that William Penn is not guilty in manner and form as he stands indicted; you say that William Mead is not guilty in manner and form as he stands indicted, and so you say all.

Jury. Yes, we do so.

Observer. The bench being unsatisfied with the verdict, commanded that every person should distinctly answer to their names, and give in their verdict, which they unanimously did, in saying,“Not guilty,” to the great satisfaction of the assembly.

Reed. I am sorry, gentlemen, you have followed your own judgments and opinions rather than the good and wholesome advice which was given you. God keep my life out of your hands; but for this the court fines you forty marks a man, and imprisonment till paid; at which Penn stepped forward towards the bench, and said:

Penn. I demand my liberty, being freed by the jury.

Mayor. No you are in for your fines.

Penn. Fines for what?

Mayor. For contempt of the court.

Penn. I ask if it he according to the fundament laws of England, that any Englishman should be fined or amerced but by the judgment of his peers or jury? since it expressly contradicts the fourteenth and twenty-ninth chapter of the Great Charter of England which says, No freeman ought to be amerced, but by the oath of good and lawful men of the vicinage.

Reed. Take him away, take him away, take him out the court.

Penn. I can never urge the fundamental laws of England but yon cry, Take him away, take him away; but ’tis no wonder, since the Spanish Inquisition hath so great a place in the Recorder’s heart. God Almighty, who is just, will judge you all for these things.

Observer. They haled the prisoners to the Bale-dock, and from thence sent them to Newgate for the non-payment of their fines: and so were their jury.

While in Newgate prison William wrote affectionate letters to his father, who was then in a declining state of health. We include two which reveal more information about the accusers and the jury.

WILLIAM PENN TO HIS FATHER.

“Newgate, 6, 7th, 1670.

“Dear Father: I desire thee not to be troubled at my present confinement, I could scarce suffer on a better account, nor by a worse hand, and the will of God be done. It is more grievous and uneasy to me that thou shouldst be so heavily exercised, God Almighty knows, than any living worldly concernment. I am clear by the jury, and they in my place they are resolved to lay until they get out by law; and they, every six hours, demand their freedom by advice of counsel.

“They [the court] have so overshot themselves, that the generality of people much detest them. I intreat thee not to purchase my liberty. They will repent them of their proceedings. I am now a prisoner notoriously against law. I desire the Lord God, in fervent prayer, to strengthen and support thee, and anchor thy mind in the thoughts of the immutable blessed state, which is over all perishing concerns.

“I am, dear father, thy obedient son,

“WILLIAM PENN.

WILLIAM PENN TO HIS FATHER.

“Newgate, 7th Sept., 1670.

“Dear Father:

To say I am truly grieved to hear of thy present illness, are words that might be spared, because I am confident they are better believed.

“If God in his holy will did see it meet that I should be freed, I could heartily embrace it; yet considering I cannot be free, but upon such terms as strengthening their arbitrary and base proceedings, I shall rather choose to suffer any hardship.

“I am persuaded some clearer way will suddenly be found out to obtain my liberty, which is no way so desirable to me, as on the account of being with thee. I am not without hopes that the Lord will sanctify the endeavors of thy physician unto a cure, and then much of my worldly solicitude will be at an end. My present restraint is so far from being humor, that I would rather perish than release myself by so indirect a course as to satiate their revengeful, avaricious appetites. The advantage of such a freedom would fall very short of the trouble of accepting it.

“Solace thy mind in the thoughts of better things, dear father. Let not this wicked world disturb thy mind, and whatever shall come to pass, I hope in all conditions to approve myself thy obedient son,

“WILLIAM PENN”