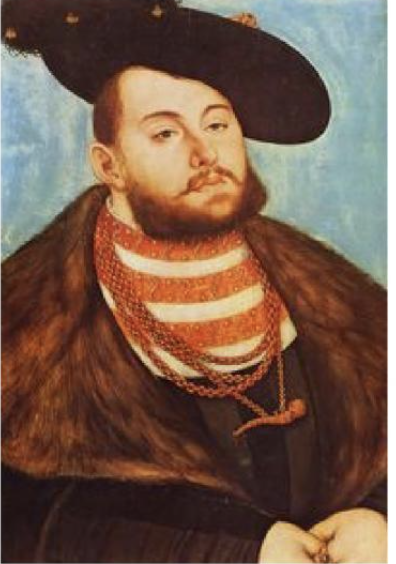

John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony, was an ardent Lutheran. Unlike others whose allegiances shifted during the religious wars that followed on the heels of the Reformation, he stayed true to his convictions. His cousin Maurice coveted his lands and the power he wielded as an elector (one of seven votes to elect future Holy Roman emperors). Maurice sided with Emperor Charles V and attacked John Frederick, but John Frederick defeated him. However, in the battle of Muhlberg a few months later forces of Charles V captured the elector. The emperor sentenced him to death.

John Frederick heard the news while playing chess. His comment was he doubted the sentence was in earnest, and returned to his chess game. Charles V was indeed using the death sentence as a bargaining chip. He compelled John Frederick to surrender Wittenberg, relinquish his electorship to Maurice, and submit to imprisonment for life.

While John Frederick was in prison, Charles tried to compel him to agree to the Augsburg Interim, which would have been to renounce his Lutheran beliefs. The prisoner refused. As a result he remained imprisoned for five years, until an about-face by Maurice forced Charles to agree to a religious settlement. Stripped of powers and lands, John Frederick was freed and returned to his wife and family.

Among his accomplishments was the founding of a school at Jena which became the University of Jena. He loved history, defended the Reformation, upheld Luther’s unusual decision to will his goods to his wife Katie, and strove for peace when possible. The main charges leveled against him were that he ate and drank too much. But Luther, Melanchthon, and Roger Ascham all spoke highly of his character and faith. Because of his stalwart refusal to renounce Lutheranism, he earned the surname “the Magnanimous.”

Here is a short extract from his response rejecting the Augsburg Interim.

[I]f I were to acknowledge and accept the Interim as something Christian and godly, then I would have to go against my conscience and deliberately and intentionally condemn and disown the Augsburg Confession and that which I have hitherto maintained and believed about the gospel of Jesus Christ in many chief articles of doctrine on which salvation depends, and I would have to approve with my mouth that which I considered in my heart and conscience to be completely and utterly contrary to the holy and divine Scriptures. Oh, God in heaven, that would be a misuse and horrible blaspheming of your holy name, and it would be like I was trying to deceive and mislead both you on high in your exalted majesty and my secular jurisdiction here below on earth with fancy words, for which I would have to pay dearly, and all too dearly, with my soul.