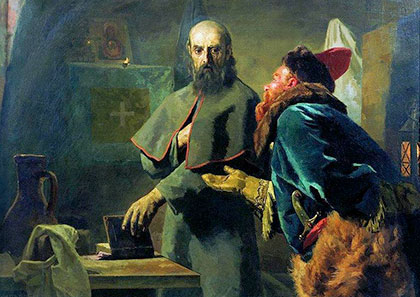

[ABOVE—Philip II, Metropolitan of Moscow and Malyuta Skuratov by Nikolaj Wassiljewitsch Newrew [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons File:Nikolaj Wassiljewitsch Newrew – Philip II, Metropolitan of Moscow and Malyuta Skuratov.jpg]

Philip of Moscow did not appear to be prison material.

Early in the reign of Ivan the Fourth of Russia, a nobleman named Fedor Kolicheff landed from a boat at the Convent of Solovetsk. He came to pray; but after resting in the island for a little while, he took vows and became a monk. A man of great abilities, he became prior of the monastery. He engaged his monks in all sorts of worthwhile projects, such as erecting buildings, cutting channels between lakes, and extracting salt from local sources. Much of what is best in the convent dates from his reign as prior.

History Of Orthodox Christianity is a detailed television presentation of the Orthodox Church, its traditions, and sacramental life. The programs aim to make Orthodoxy better understood among those who are unfamiliar with this ancient Christian Church.

He had been a friend of young Ivan, soon to be known as Ivan the Terrible. Ivan sometimes called him to the Kremlin to give him advice. On these occasions, Philip was aghast at the change in the Tsar; who, from being a paladin of the cross, had settled down in his middle age into a mixture of the gloomy monk and the savage Khan, engaging in orgies and sodomy, and delighting in torture. The change came on him with the death of his wife and the conquest of Kazan; after which events in his life he married two women, dressed himself in Tartar clothes, and adopted Asiatic ways. Like a chief of the Golden Horde, he went about the streets of Moscow, ordering this man to be beaten, that man to be killed. The square in front of the Holy Gate was red with blood; and every house in the city was dewed with tears.

Then Ivan summoned Philip from his cell near the frozen sea to occupy a loftier and more perilous throne: Metropolitan of Moscow. He had driven out two aged prelates who rebuked his crimes, and thought Philip would shed a luster on his reign without disturbing him by personal reproof. Philip tried to escape this unwelcome assignment; but the Tsar insisted on his obedience; and with heavy heart he sailed from his asylum in the islands, conscious of going to meet his martyr’s crown.

Ivan had misjudged Philip, who was not one to speak smooth words to princes. For instance, in traveling from Solovetsk to Moscow, he passed through Novgorod; a city disliked by Ivan on account of its wealth, freedom, and laws. A crowd of burghers poured from the gates, falling on their knees before him, and imploring him, as a pastor of the poor, to plead their cause before the Tsar, who threatened to ravage their district and destroy their town. On reaching Moscow, Philip spoke to Ivan as to a son; beseeching him to dismiss his guards, to put off his disgusting habits, to live a holy life, and to rule his people in the spirit of their ancient dukes.

Ivan was furious; he wanted a priest to bless him, and not to warn. The tyrant grew more violent in his moods; but the new Metropolite held out in patient and unyielding meekness for the ancient ways. This led to many confrontations between them, and with such a tyrant, the end was predictable.

The Assassination of Philip, adapted from Free Russia by William Hepworth Dixon

As every man in trouble went to the Metropolite for counsel, the boyars accused him of inciting the people against their prince. When Ivan married his fourth wife, a thing unlawful, the Metropolite refused to admit the marriage, and bade the Tsar absent himself from mass. Rushing from his palace into the Cathedral of the Annunciation, Ivan took his seat and scowled. Instead of pausing to bless him, Philip went on with the service, until one of the favorites strode up to the altar, looked him boldly in the face, and said, in a saucy voice, “The Tsar demands your blessing, priest!”

Paying no heed to the courtier, Philip turned round to Ivan on his throne. “Pious Tsar!” he sighed; “why are you here? In this place we offer a bloodless sacrifice to God.” Ivan threatened him, by gesture and by word.

“I am a stranger and a pilgrim on earth,” said Philip; “I am ready to suffer for the truth.”

He was made to suffer—and soon. Dragged from his altar, stripped of his robe, arrayed in rags, he was beaten with brooms, tossed into a sledge, driven through the streets, mocked and hooted by armed men, and thrown into a dungeon in one of the obscurest convents of the town. Poor people knelt as the sledge drove past them, every eye being wet with tears, and every throat being choked with sobs. Philip blessed them as he went, saying, “Do not grieve; it is the will of God; pray, pray!” The more patiently he bore his cross, the more these people sobbed and cried.

Locked in his jail and laden with chains, not only round his ankles but round his neck, he was left for seven days and nights without food and drink, in the hope that he would die. A courtier who came to see him was surprised to find him engaged in prayer. His friends and kinsmen were arrested, judged, and put to death for no offence except that of sharing his name and blood.

“Sorcerer! Do you know this head?” was one laconic message sent to Philip from the Tsar.

“Yes!” murmured the prisoner, sadly; “it is that of my nephew Ivan.” Day and night a crowd of people gathered round his convent-door, until the Tsar, who feared a rising in his favor, caused him to be secretly moved to a stronger prison in the town of Tver.

One year after the removal of Philip from Moscow, Ivan, setting out for Novgorod, called to mind the speech once made by Philip in favor of that city and sent a ruffian to kill him. “Give me your blessing!” said the murderer, coming into his cell.