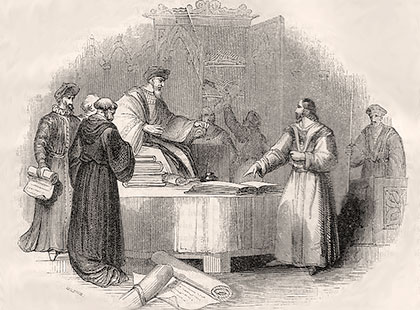

[ABOVE—“The Examination of William Thorpe,” from John Foxe’s The Acts and Monuments of the Christian Church (John Cumming, 1851).]

The Testimony of William Thorpe was well-known from the fifteenth century. It tells of Thorpe’s arrest and confrontation with a hidebound religious system. A century later, John Foxe included Tyndale’s “modernized” version in his Actes and Monuments, or the Book of Martyrs. Although the manuscript dates from Thorpe’s time, scholars now question whether Thorpe ever existed, as there is no independent confirmation of his appearance before Archbishop Arundel and the manuscript is a fairly polished work. However, men of the era accepted it as authentic, as did William Tyndale in the following century, and it is, at the very least, an authentic picture of what Lollards believed and suffered.

Archbishop Arundel was the prelate who drafted the law which prohibited English Christians from possessing scripture and who had the Lollard priest, William Sawtrey, burned to death as a heretic. Lollards were advocates of John Wycliffe’s reforming ideas.

One of Europe’s most renowned philosophers and scholars, John Wycliffe chose to serve the common people and risked himself to provide the Scriptures for the people.

Thorpe also was a Lollard. He sparred with Arundel, gave a lengthy testimony to Christ, and defended his Lollard beliefs, agreeing only to accept any teaching of the church which agreed with the words of Christ and the apostles. Arundel declared him a heretic and sent him to prison.

John Foxe, unable to locate any record of Thorpe’s end, thought it most likely the man was secretly made away with or else died of sickness in his dungeon. The version below is given in modern English.

Excerpt from the Testimony of William Thorpe.

Then after a while the archbishop said to me, “Will you not submit to the ordinance of holy church?”

And I said, “Sir, I will gladly submit myself, with the stipulations I gave you before.”

Then the archbishop ordered the constable to take me away quickly.

And so I was led out then, and brought into a foul, dishonorable prison, where I had never been before. But thanks be to God, when all men were gone away from me, and had barred fast the prison door after them, and when I was alone, I busied myself with thinking on God, and thanking him for his goodness. And I was then greatly comforted in all my thoughts, not only because I was delivered for a time from the sight, from the hearing, from the presence, from the scorn, and from the menaces of my enemies; but much more I rejoiced in the Lord, because through his grace he kept me so that, despite the flattery (especially), and despite the threats of my adversaries, I got away from them without heaviness and anguish of my conscience.* For as a tree laid upon another tree athwart or cross-wise, so were the archbishop and his three clerks always contrary to me, and I to them.

*He means he would have had a bad conscience if he had yielded to their threats and betrayed the truth.